Support Our Work

Contact Information

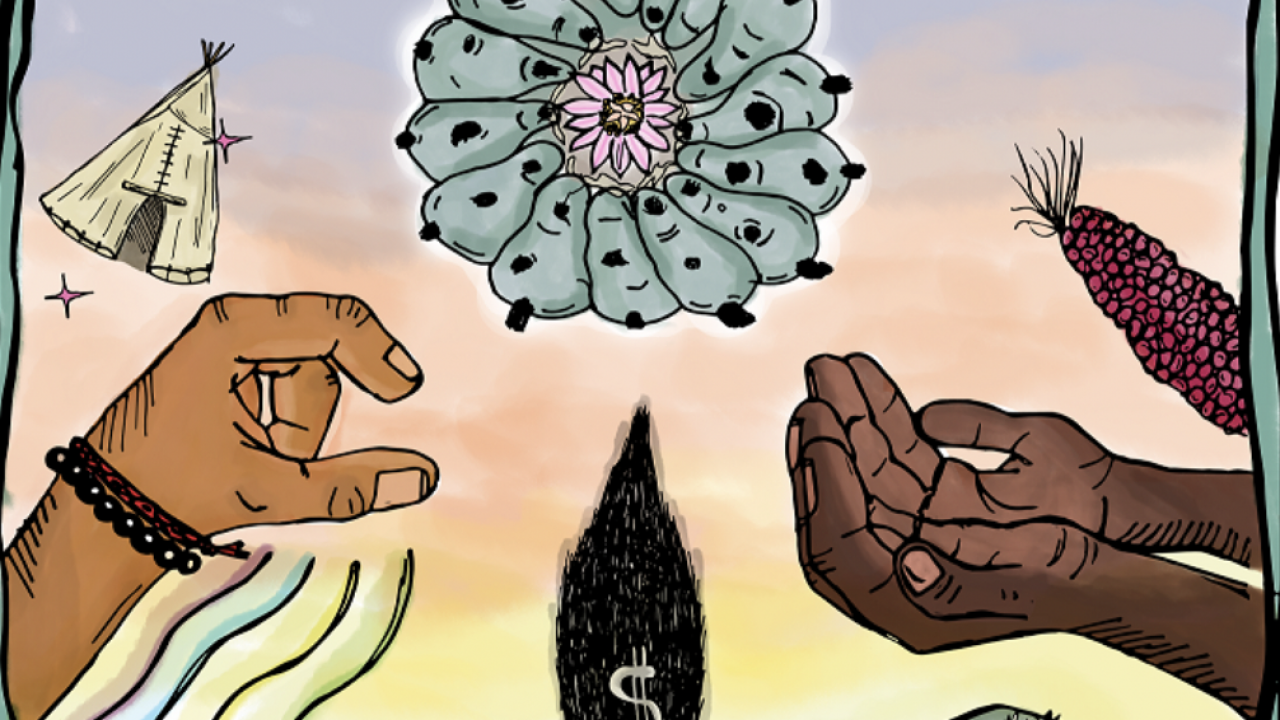

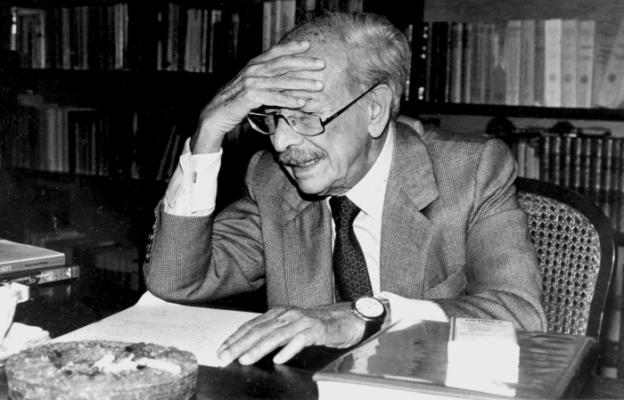

Wixárika Research Center

Telephone: (510) 420-1231

inquiries@wixarika.org

Website Contact Form

"We are committed to the defense of the sacred lands and natural resources of the Wixárika people"

Juan Negrín, Founding Director, Wixárika Research Center