Tutukila Carrillo Sandoval

Tiburcio Carrillo Sandoval was born on a ranch in Tuapurie (Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán) in 1949, where he received the name Niukame, or “Sprouting Corn” or corn shoot. By the time he and Juan Negrín met in 1972, he had adopted the pseudonym Tutukila to sign his artwork. This name derived from tuutú, a yellow flower that is associated with corn, and kixa, the action of beating the cornstalks with a stick to release the pollen or dust before the harvest. In 1963, he became one of the first members of his community to begin a formal education, finishing seventh grade outside of Wixarika territory to finish seventh grade.

He started making yarn paintings in Zacatecas as an apprentice to a fellow tuapuritánaka (member of the Tuapurie community), Andrés Valenzuela. He commented, “Andrés never wanted to teach me how to work properly, but by observing him I dedicated myself to forming certain figures, as a game or for a decorative effect. With time my designs improved, although they remained crude.”

In 1964 he went to Guadalajara seeking work as a craftsman. There he met the unforgettable craftsman and artist Ramón Medina Silva, who was working with Father Ernesto Loera who was then the head of the Basilica of Zapopan in the Guadalajara metropolitan area. Medina, whose compositions were treatments of meaningful themes, hired Tutukila to assist him in making yarn paintings. It was this experience that sparked his interest in illustrating Wixarika mythology.

After four months, Tutukila returned to the Sierra Madre highlands to further his knowledge about his own culture by asking his father pertinent questions. His father responded by telling him that he would give him the proper orientation later if he showed an earnest interest in his people’s history. Consequently, Tutukila pursued his religious education by visiting the sacred places of Our Ancestors across Wixarika territory. Tutukila interviewed wise elders in his community, but he emphasized to Negrín that “Even in these last few years, none of them has ever told me the truth; so I have relied on my own insight and the teachings of my father.”

While he created paintings with Negrín's sponsorship, Tutukila performed special rites and sacrifices for revealing aspects of his culture to the broader world, which he did in the hope that Wixarika culture would receive more respect and recognition. He introduced Juan and Yvonne Negrín to life in the most remote parts of the Wixarika Sierra, and they eventually became the compadres of two cousins of his, Totopika and Hautsima. Totopika held considerable prestige as the Secretary of Communal Goods ; he was the intermediary for the Wixarika people with the federal government and managed to make personal contact with President Luis Echeverría (1970-1976) in the attempt to solicit help for his people.

Because of the Negrín's close bonds with the Tuapurie community, when Totopika died in 1979, the community asked Juan by consensus to be its adviser in blocking the government’s efforts to take away their land and to plunder their forests in collusion with private lumber companies. The mutual understanding between Tutukila and Juan was formed within a vast context of interactions, which drew Negrín to serve Wixarika communities until his death in 2015.

Tutukila stressed the ethic of not revealing the truth to those who have not reached religious maturity through active practice and rigorous devotion on a long-term basis. Our Ancestors often achieved their ends by resorting to trickery and by testing those who sought their help. Today the wise mara'akate (chanters), having gained their knowledge through penitence and discipline, will not instruct others who seek knowledge gratuitously.

Along with José Benítez Sánchez, Tutukila was in the 1970s the main inspiration for the evolution of yarn paintings into a genre of art that depicted Wixarika tradition. However, his approach to the medium reflected a different background than that of José Benítez, and a more didactic viewpoint.

When Tutukila collaborated with us from 1973 through 1975, he produced an epic history of the feats of Our Ancestors in a series of yarn paintings that averaged 10 per story. He incorporated carefully gathered information from close relatives who were noted shamans. He was recognized for his peerless craftsmanship, which he used to carefully detail important symbols and to forcefully represent the prototypal figures of Our Ancestors, thus influencing changes in the style of his fellow yarn painters.

His intricate manipulation of detail gave more realism to his figures than is found in the work of José Benítez and others. He slowly formed the figures in his compositions, working with great application and concentration, without sketching any outlines on the beeswax (unlike Benítez). Even when creating large paintings, he rendered all the major features of each figure before beginning to form the next one. The color field that surrounds his figures follows their contours carefully, creating unique linear patterns that radiate from their forms and integrate them into the overall composition.

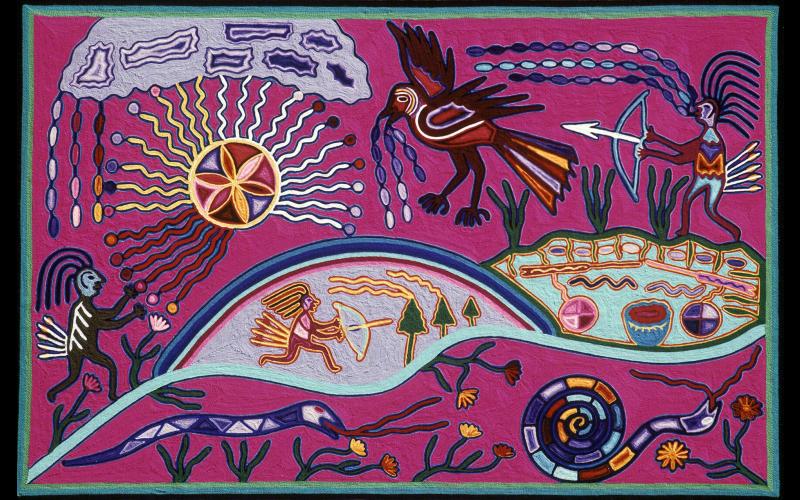

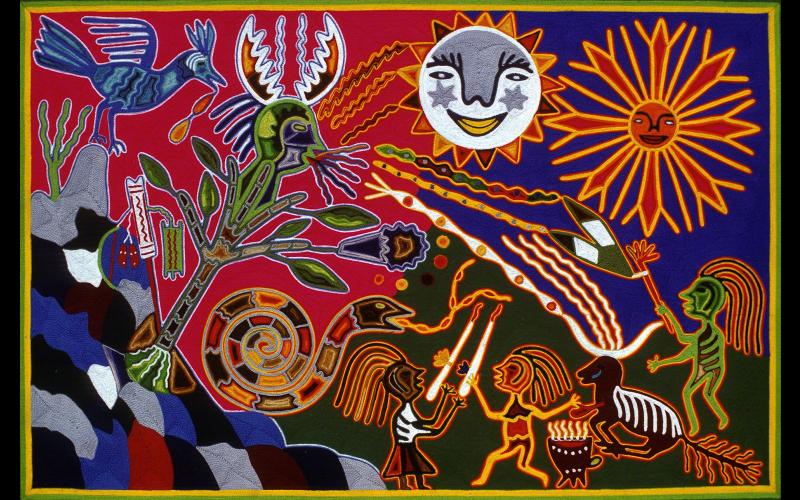

Tutukila’s vibrant, harmonious textural approach confers an inner vitality on his figures. The Petrified Figure of Our Grandfather Fire (2' × 2', 1973) and The Power of the Kieri Is Tested (4' × 2', 1974) are two examples of his diverse style. He found it difficult to enlist the help of equally meticulous apprentices, and worked mostly by himself or with his wife Turuima.Tutukila’s art is more reflective and style-conscious than José Benítez’s, partly because he aimed to depict his themes in faithful detail. He viewed his art as an effort to capture the significance and richness of his culture, having been made painfully aware that other Mexicans and outsiders regard his people as ignorant members of an inadequate society. He hoped mestizos and young Wixaritari would come to realize the depth and validity of their culture.

“We cannot develop well among the mestizos because they don’t understand our religion or our culture and they don’t realize how we would suffer, if we lose our traditional ways and become just like them. But I say it is not right to lose everything that is ours in exchange for something we can’t defend. Outside culture is important, but so is ours. I believe we are losing it, now the young are losing their very language!”

Tutukila eventually chose to use his teaching credentials to become a supervisor of the National Indigenous Institute’s bilingual school programs in the state of Nayarit. He died on June 27, 1997, from a heart failure and liver ailments, according to his last wife, Margarita.

Text ©Juan Negrín 2003 -2024, All rights reserved digital and print.

Photographs ©Lloyd Patrick Baker