José Benítez Sánchez

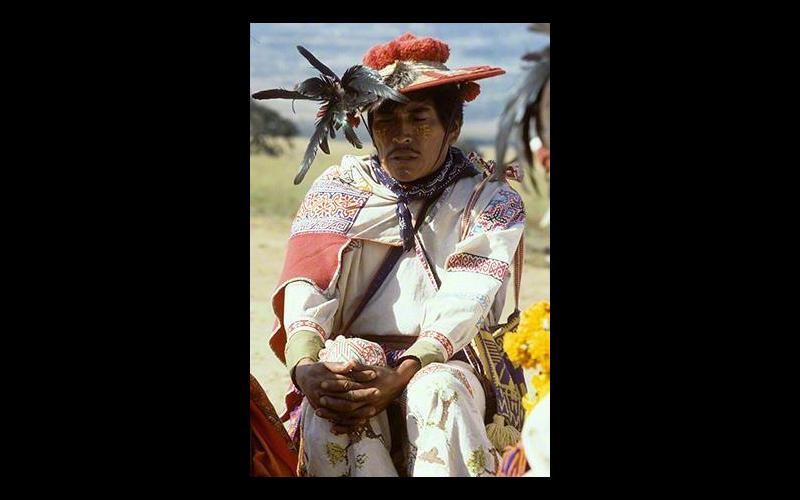

José Benítez Sánchez was born in 1938 on a ranch called San Pablito in Nayarit and given the name Yikaiye Kikame, “Silent Walker,” in the Wixárika language.

In our efforts to meet the more gifted artists and learn what they could tell us about their artwork’s symbolic and legendary meanings, we ventured into different parts of the states of Jalisco and Nayarit, where the Wixárika communities are concentrated. In 1971, we met José Benítez Sánchez, who had set up his workshop in Tepic, Nayarit, and whose reputation as a yarn painter was beginning to eclipse that of most of his peers.

He was born in 1938 on a ranch called San Pablito in Nayarit and given the name Yikaiye Kikame, “Silent Walker,” in the Wixárika language. His religious tradition and family ties link him to the Wixárika subgroup of Wautia (the community of San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán). He was brought up by his maternal grandfather, who died at the age of 105, leaving a strong impression on José’s memory, and his stepfather, Pascual Benítez. Both of them were mara’akate (shamans).

Following the proper disciplines with his stepfather and his grandfather, José worked in the fields when he was eight; the next year, his stepfather decided to train him as a shaman. He caught a deer in a snare before it died; this was a good omen. He was told to breathe in the last exhalations of the sacrificial deer and thus began to initiate a shamanic career by the age of nine. Afterward, he was instructed to go into mourning for the deer for six years, during which time he should not touch a woman or spice his food with salt.

During the next four years, José Benítez made yearly pilgrimages to Our Mother Ocean and to the sacred places in the canyons deep in Wixárika ancestral territory. When he reached the age of fourteen, however, his stepfather died and he was forced by his relatives to marry, according to Wixárika custom. Soon thereafter, he ran away, seeking work in the coastal fields and entering Mexican society without knowing any Spanish. Benítez said, “When I started working as a coastal laborer, I left my Wixárika clothes and my sandals, changing them for Mexican clothes, and I soon felt like a mestizo. I never forgot my traditional customs, but it was not the same, because I had abandoned my plans for becoming a mara’akame (shaman).”

It was not long before Benítez came in contact with government agents involved in rural communities and began working for them in various capacities, sweeping their offices and eventually traveling to every community in the Sierra and its foothills, as a spokesman for the Mexican authorities. During this time, in 1963, he started to try out his skills at making yarn paintings: “I could not draw the figures as they ought to be represented, but I began to think back about the lives of my grandparents, my parents and our traditional customs.” By 1968, he was recognized as one of the foremost practitioners of Wixárika arts and invited to play music and dance with other companions during the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City. In 1971, he was still working for the government through its Coordinating Center for the Development of the Huicot[1] Region. Besides producing his own yarn paintings, he was a middleman between the government and those Wixaritari whom he trained or whose crafts he sold through the government offices.

By 1971, José Benítez came to be recognized as an undisputed master of original dramatic compositions, and his knowledge of the culture was respected by other craftsmen specializing in this medium. Many copied his style as best they could, a few achieving personal touches that kept their own work original. Benítez remains unsurpassed in the abundance and inventiveness of his art over the long span of his evolving career. The first craftsmen who introduced me to Benítez touted him as an important shaman, although Benítez told me soon afterward that he had not really achieved that status yet. Towards the beginning of this millennium, he claimed to have reached this status, after many pilgrimages and related sacrifices.

In his earlier years of work, Benítez had taught several dozen Wixaritari how to make yarn paintings. His apprentices were Wixaritari who had become urbanized enough to eke out a living without depending entirely on their subsistence-farming tradition. Among them, Juan Ríos Martínez mastered his own forms and style and went on to produce beautiful and original compositions. Others worked out a superficially personal style while basically sticking to simple compositions that they had at one time helped their teacher produce, filling in the background for the figures that Benítez had already designed. It became apparent to us that José Benítez was the anonymous living source of the designs produced by many other artists and craftsmen.

By 1972, my wife, Yvonne, and I were residing permanently in Mexico and working with many Wixaritari. Most significantly, at that time I made my first forays into the deepest canyons of the Western Sierra Madre—to Teakata, the temple of Our Grandfather (Fire)—with Benítez, who had begun his initiation there as a youth. Circumstances had interrupted his shamanic practice until we returned together. This led to many ensuing pilgrimages to the sacred places of power in the mountains, to the peyote desert in the East, to Our Mother of the Ocean in the West, and to Our Mother of the South Waters. José and I participated under the direction of two shamans, who were brothers, Yauxali and Matsiwa, or Pablo and Francisco Taizán de la Cruz, exercising the functions of mara’akate, shamans, in the community of Tuxpan de Bolaños and in Mesa del Tirador, annexes of San Sebastián Teponahuaxtlán, Wautia.

Eventually, José Benítez’s artistic expression became more complex, and I became more able to distill a deeper meaning from his works due to our shared experiences. As a result of our pilgrimage in early 1972, he dedicated himself exclusively to developing his artistic talent and renewing his links with his religious tradition. His pending vows would persecute him in agitated dreams until he externalized them as visual images, and we eventually reached the time where the sacred offerings had to be taken again. That experience would lead to many more visionary understandings of traditional reality.

Together, we went on five journeys to Wirikuta, in the East. On three occasions we walked and fasted in the desert for seven days, and walked several times to the most holy spots in the mountains: Tuamuxawitá, the cave of the First Cultivator; Ni'ariwametá, the falls and the niche of Our Mother the Messenger of Rain; Teakata, the prototypal ceremonial center above the birthplace of Our Grandfather (Fire). We went to the edge of Our Mother Ocean by the white peak in the sea called Waxiewe, Our Mother Who Is like White Vapor Escaping, and to Xapawiyemetá, the lake in the South named after its wild fig tree, where it is said that the new earth first appeared after a five-year flood.

Benítez took extended breaks from pursuing his art when he undertook these pilgrimages, and eventually reintegrated himself into the Wixárika community of Wautia, where he followed the tradition of cultivating the land and participating in all the ceremonial rites attached to that cycle. At that time (the early 1980s), the artist said “This is how the xutúrite (the flower offerings)[1] suffer: without food or sleep, without possessions or knowing where they are headed, poor and innocent, but rich in their kipiri (soul) and in their tukari (spiritual life or vital energy).”

In a composition he wrote for a Wixárika xaweri, a native adaptation of a violin, he chants in praise of Tamatsi Kauyumarie, Our Elder Brother Fawn of the Sun, saying, “My Elder Brother’s word and his figures, his designs, his thought is never-ending in the drawings of his matsiwate (wrist guards or bracelets) and in his 'uxa' (the yellow pigment painted on his face).”

He was conscious that many of the yarn paintings he produced in partnership with me are reflections of the ancestors, and he said, “Our memory will stay in these paintings.” These were visual expressions of what Benítez had learned under the spiritual guidance of Our Elder Brother, which he wanted me to understand in depth by tape-recording explanations that allowed me to pursue their meaning in detail.

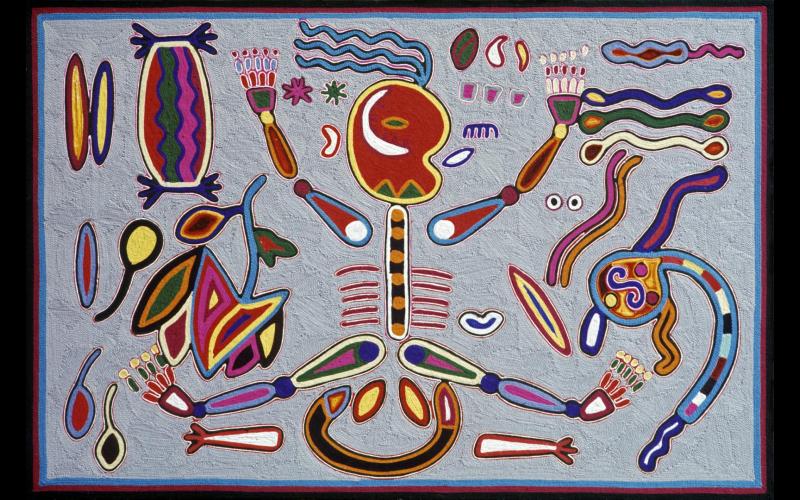

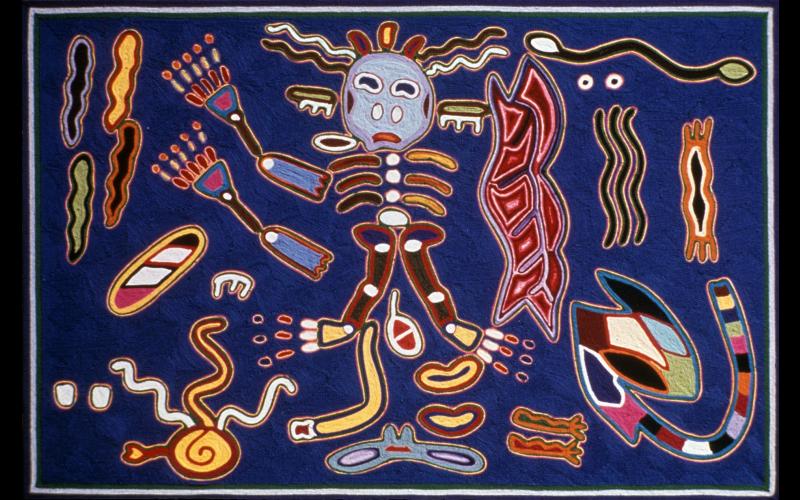

Important traditional shamans from the mountains have visited me, and they are often struck by the lucidity of Benítez’s work, reflecting deeply on its meaning in their own way. His art underwent firm changes until 1982/85, when wool yarn and the native bee’s wax used to hold it in place disappeared. His figures have always been bold and dramatically placed in dynamic juxtapositions, with a deep understanding of color and contrast (see The Four Aspects of the Spirit, a 2' × 2' yarn painting above). They started out as relatively ingenuous depictions and within a few years became more complex, as well as more intricately connected.

José Benítez created some pieces in a 4' × 2½' size, like The Dismemberment of Our Great-Grandmother Nakawé and The Dismemberment of Watákame, from 1973, which show surprising parallels to the finest works of surrealistic and contemporary fine art. He evolved from a classical to a more baroque style, as his narratives became more complex, and his inventiveness was invigorated by the many pilgrimages and his return to his roots. Another painting of this size from 1979, titled The Nierika of Our Great-Grandfather Deer-Tail, exemplifies this inspired complexity. By 1980, José Benítez’s art had become extremely sophisticated, and the meaning was difficult to extrapolate from his greatest work. A good example of this is his 4’ × 8’ yarn painting from 1981, called The Transcendental Vision of Tatutsí Xuweri Timaiwe’eme (Our Great-Grandfather Who Was Self Created and Found Knowing Everything). It toured many world museums until it was donated to the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City, for permanent exhibit, in September of 1999, by George H. Howell, who had purchased it from me.

A constant characteristic of Benítez’s art is that his figures are abstract enough to remain symbolic prototypes, yet are reproduced in many unique variations, transformed by the presence of other figures in a context that is full of interlinking energy fields and sharp contrasts. His strong sense of rhythm and balance reflects his early skill in performing Wixárika music and dances. He used both thick and thin wool yarn to achieve rich textures and to avail himself of the widest range of color tones, later he used thin acrylic yarn to develop a style that can be creatively baroque or more symmetrically ornate.

In the late 1980's, the artist left the community of Wautia, after a short stay. He then moved back to Tepic and fought for the rights of many Wixaritari who lived on the periphery of the small city. In the 1989, Benitez and other Wixárika residents successfully had the neighborhood where they lived renamed Colonia Zitakua, which is today a refuge for many Wixaritari displaced by the Aguamilpa Dam in the early 1990s or who have left their rural communities to pursue making arts and crafts in the city. Zitakua has its Wixárika tatoani, or governor, and a tuki, or round temple, at the top of a hill on the outskirts of Tepic.

Although the public in general has still not properly recognized him as one of Mexico's great artists since the presentation of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City, in 1986, Benítez always resisted anonymity. In 2001, he created the largest yarn painting to date, which was commissioned by the government and placed behind a glass frame in the Juarez subway station in Guadalajara. In 2003, the Museo Zacatecano of Zacatecas gave prominent display to one of his circular 4' × 4' paintings, and he received the national prize of “Ciencias y Artes”, Sciences and Arts.

José Benítez Sánchez lived a remarkably intense life, full of experiences, responsibilities, abundance and service. His charisma was such that he attracted many followers, companions and created a large family. He would tell me a couple of years before his death that he probably had more than fifty grandchildren.

Benitez passed away in Tepic on July 1, 2009, a few days after an unsuccessful surgical attempt at saving his life.

Text by Juan Negrín

[1] “Huicot” stands for the Hispanicized Huichol, Cora, and Tepehuano Indigenous names and denotes their shared geographic region that includes portions of the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, Durango, and Zacatecas.

[2] Xutúrite are natural or paper flowers attached to an offering, and also the nickname for the Wixaritari in the language of Our Ancestors.

Text written by Juan Negrin (2002) and edited by Diana Negrin (2020). Texts and photographs Copyright ©2002 - 2023 Juan Negrín. All rights reserved.