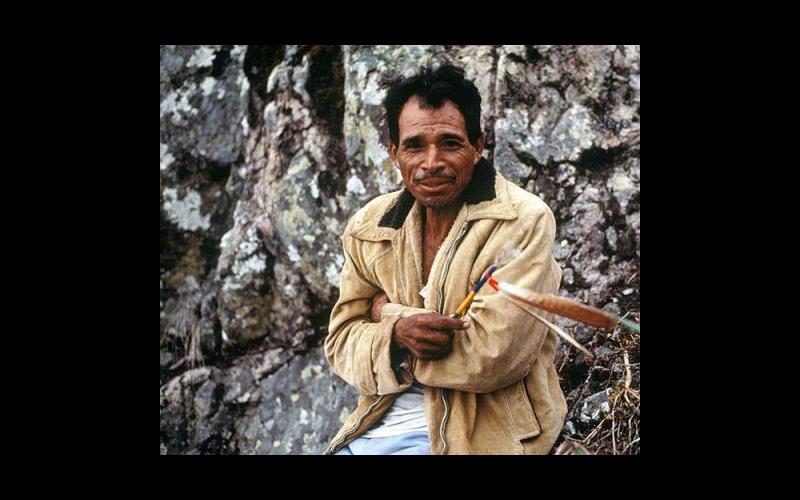

Guadalupe González Ríos (Ketsetemahé Teukarieya)

Guadalupe González Ríos (1923 - 2003)

Guadalupe González Ríos, Ketsetemahé Teukarieya, or “Godson of the Mounted Iguanas,” was born on December 12, 1923 in the Wixarika settlement of Carretones de Cerritos, Nayarit. He considered himself a member of the community of Tuapurie (Santa Catarina Cuexcomatitlán) through his father’s tradition.

One of his grandfathers, Inés Ríos, became a legend among the Wixaritari. He was a teiwari, i.e., a “neighbor,” as the Wixarika call someone who is of mixed heritage or a community outsider, but he discovered a plant that the Wixaritari consider a very powerful means of achieving shamanic capabilities.

This solanaceous plant (related to the nightshade family) has very strong hallucinogenic properties and is known to the Wixarika as kieri, or the tree of the wind. Unlike peyote, which is found in the eastern desert and is associated with the insight of Dawn and the Sky, kieri is purported to transmit a transcendental means of perception, a nierika, for penetrating the darkness of the Underworld, the flesh, and matter. This western cosmic realm is related to Our Mother Ocean where Our Father descends at dusk and to the Journey of the Dead. Kieri can bestow the power to heal or to hex effectively as well as to play extraordinary music and to become a great mara'akame (chanter and healer), and this can be achieved more rapidly than with peyote. At the same time, kieri is reported to be extremely dangerous by comparison.

It takes an earnest and humble man like Guadalupe González to master the complexities of being a devotee to this plant that his grandfather passed on to him. The kieri drew his grandfather into the world of Wixarika religion and ceremony as an unsurpassed master violinist. He was deemed to be able to play in several places at once! The Mexican anthropologist Dr. Jesús Jáuregui, who did his thesis on the roots of mariachi tradition in Mexico, investigated the story of Inés Ríos and wrote about him and his musically gifted descendants. (1) But unlike his grandfather, or his cousin Juan Ríos Martínez, Guadalupe González did not acquire musical gifts from going to the kieri; he was more involved with its healing power.

Guadalupe González had been warned by one of his uncles that if he reproduced meaningful designs in his yarn paintings, he would eventually become blind. Two factors could mitigate these consequences: the first, that his work not be used for merely decorative purposes, but to arouse respect and admiration for Wixarika culture; the second, that Juan Negrín, who was commissioning the yarn paintings, would submit himself to the sight of his principal master, a kieri that is particularly feared, growing on top of Tukakamerixi, four large peaks on the western rim of the Wixarika territory that represent the Lords of the Underworld. From there, at the end of a long pilgrimage, one overlooks the Gates of the Underworld in Our Mother Ocean, as Our Father (Sun) is swallowed to begin his invisible course from the West to the East through the serpent’s trail below.

Guadalupe González took Juan Negrín on three journeys to Tukakamerixi between 1973 and 1977, and Negrín began to recognize that the power of the kieri was more than myth. Guadalupe González had been exclusively involved in the cult to the kieri until he made a pilgrimage with Negrín to Wírikuta, under the guidance of artist and mara'akame Yauxali, also known as Pablo Taizán. González continued these pilgrimages from his ranch site, initially at Las Blancas, near the foot of the peaks and later from Las Pilas, near the Salvador Allende Wixarika land grant in Nayarit. He lived more at ease in these ranches with his wife, Francisca, and their children than in Tepic where he spent periods of steady work making arts and crafts.

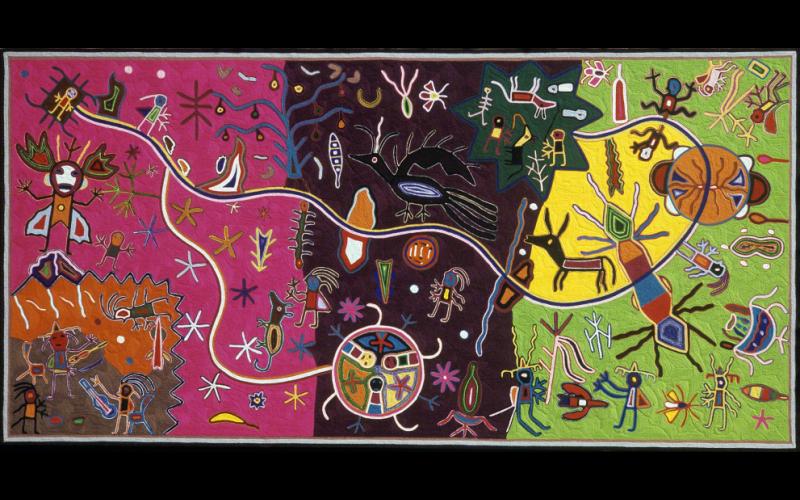

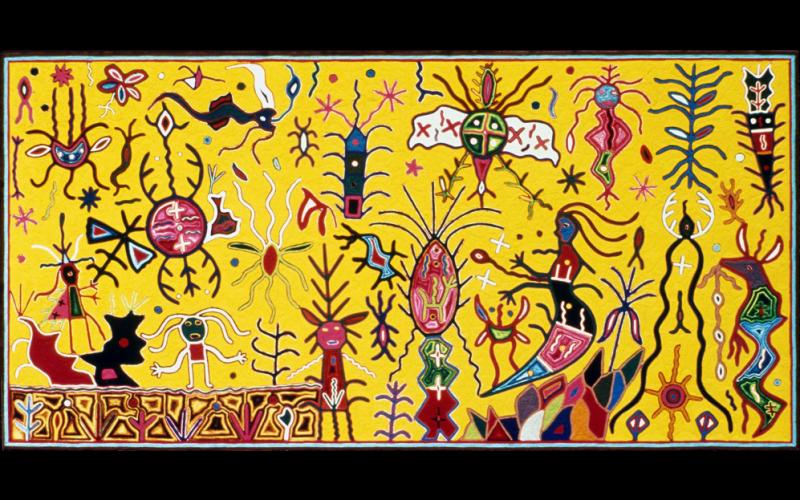

González’s masterpieces have little in common with the work of José Benítez. In González’s paintings, figures are not connected to each other by linear relationships. Instead, they reflect and emanate a mystical attitude. Human prototypes appear to float in a vacuum, often defying gravity and a preconceived sense of space. The focal point is the central being of the ancestor invoked in the yarn painting, around which everything else is arranged. Points, stars, and other symbols represent various prayers, and multiple beings invoke the legendary figures and their allies.

Guadalupe González’s use of color can be very bold, and his figures are connected by the rhythmic pulsations created by the words and prayers (dots, stars, etc.) and the resonance of larger circular figures representing nierikate. (2) His major paintings are often large, typically 4ft by 4ft, such as The Birth of Our Father Sun (1973), The Birth of Our Great-Grandmother Moon (1973), The Birth of the Tree of Wind (1974), and The Metamorphosis of the Petrified Ancestor (1974). He created two other masterpieces in an even larger, 4ft by ft size, one of which is The Journey of the Dead (1974).

After 1976, Guadalupe González was more dedicated to practicing his healing skills than to creating yarn paintings and produced few equivalent masterpieces. Some westerners availed themselves of his capabilities, and for several years in the 1990s he traveled to various parts of the United States as a healer. But he soon stopped this work because he did not feel comfortable in that capacity. He continued to lead a small group of outsiders on pilgrimages until he was no longer physically able to do so.

He became too old to create yarn paintings, because his physical condition prevented him from exerting the necessary tension and constant pressure in applying each strand of yarn with the fingertips. But on occasion, he would still create a special work of art to focus his energy and stop the tremors in his arms and hands. Guadalupe González died on May 18, 2003 in a hospital in Tepic after a prolonged illness. His art remains exceptional among the Wixárika and in contemporary fine art and two of his sons, Cristóbal and Fermín González, remain active yarn painters.

1 “Un siglo de tradición mariachera entre los huicholes,” from Música y Danzas Del Gran Nayar, which he edited for the Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos and the Instituto Nacional Indigenista, México, in 1993.

2 Plural for nierika

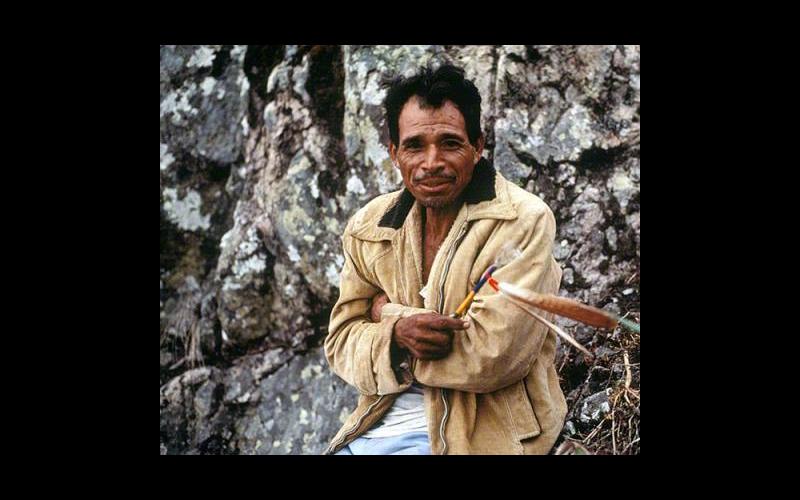

Text and photographs ©Juan Negrín. All rights reserved digital and print.