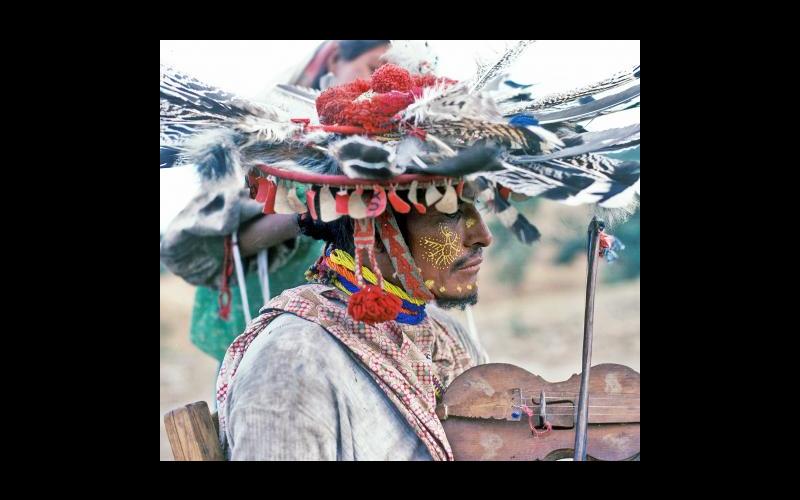

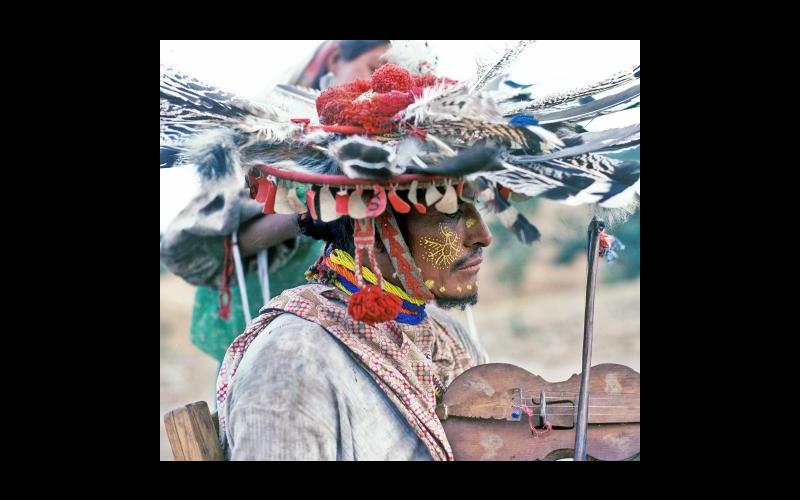

Yauxali

Pablo Taizán de la Cruz (1936-2016) is also known by his Wixarika name, Yauxali, that means “the clothing of Our Father (the Sun)”. He was born around 1936 in an extended ranch called Taimarita in the community of Tuapurie; when he was young, his family moved toward the south of the Wixárika region to Tuxpan de Bolaños or Kuruxi Manuká. Along with his brother, Francisco, Matsiwa, he found refuge among his Wautia siblings and together they became experts in the shamanic arts, capable of leading pilgrimages to remote sacred spots and chanting sacred praises to Our Ancestors that lasted for days and uninterrupted nights. Both Yauxali and Matsiwa were healers as well. Unlike other artists profiled in our archive, Yauxali was first recognized as a singer and pilgrimage guide first in his adoptive community of Mesa del Tirador, and later among international spiritual circles.

Yauxali did not begin to lead ceremonial chants after some twenty years of uninterrupted discipline and pilgrimages. Many of his foot pilgrimages traced the entire path from the coast in the West to the eastern holy land of Wirikuta, as well as through the northern and southern sacred places. The mara'akame (chanting and healing shaman) can represent Our Ancestors as they are: in the esoteric symbolism of votive objects like urute, votive arrows, and xuk+rite, gourd bowls; nierikate, wooden disks decorated with yarn; and memuute or tepárite, standing or round sculptures in stone. Long, intimate experiences of the sacred allow the shaman to draw precisely from a great range of symbols to describe his visions in properly assembled ideographic compositions.

In 1975, during a pilgrimage to the cave of Tuamuxawi, the First Cultivator, where Yauxali was Juan Negrín’s guide, Negrín was impressed with a beautiful carved wooden head of a deer. Yauxali said he had left it during a previous occasion as an offering because he had fainted when he was working the fields and a deer’s head was revealed to him. Tuamuxawi urged him to reproduce the vision and take it to the cave. Throughout his life he would subject himself to ritual disciplines and, by the end of the 1970s, together with his brother Matsiwa, he began to work on a collection of sculptures representing copies, in some cases, of erect quarry stones, memu’ute, and their circular equivalents or altars, tepárite.

Yauxali began to make wool yarn paintings in 1978 as part of an effort to explain the role of Our Ancestors and their iconography in Wixarika history. He became a rare exception among yarn painters: an expert mara’akame who approached his work as a master of purely sacred art. His output was sporadic, and his explanations were couched in esoteric shamanic vocabulary. The best of his art contains the same energy and sincere conviction of Guadalupe González’s finest pieces, as if a hidden magnetism guided his hands, and the artist allowed himself to become an impassioned intermediary for the messages of Our Ancestors. Yauxali’s greatest yarn paintings are meant for people initiated in Huichol culture, but their archetypal beauty breaks down cultural barriers with its universal appeal.

Following subsequent pilgrimages, in 1977, Yauxali and his brother Pancho (also known by his Huichol name, Matsuwa, which means “wrist-guard”), began a special project with Juan Negrín to produce stone carvings of the sacred figures of Our Ancestors. These were to be kept as a repository of symbolic guideposts for future generations of Wixaritari. With Negrín, Yauxali and Matsiwa founded the non-profit organization, La Asociación para la Preservación Del Arte Sagrado Huichol, A.C. (The Association for the Preservation of Sacred Huichol Art) in Guadalajara, Jalisco, and received funding for the purchase of the first sets of standing sculptures, memu’ute and the round sculptures that accompany them, tepárite. Cultural Survival, Inc. in Cambridge, Massachusetts, provided most of the initial funding through Friends of Huichol Culture, Inc., both nonprofit organizations established in the United States. The remainder was covered through personal donations by the Negríns.

Some of Yauxali’s works are at the Radford University Collection in Radford, Virginia, along with a number of works by the same artists in our archive, such as José Benítez, Guadalupe González, Juan Ríos, and Tutukila. There, in a retreat center on campus, is Tatéi Niwetsika, Our Mother Corn, standing erect in volcanic white stone, next to her tepari, a round carved stone shield through which she can perceive her realm. These are Yauxali’s only publicly displayed sculptures outside of Mexico. Yauxali sculpted these pieces and their appropriate symbolic offerings: a votive arrow, a gourd bowl, and an accompanying nierika. The art collection was donated to the university by the Kolla-Landwehr Foundation in 1996, thanks to the coordination and patronage of John H. Bowles. Yauxali spent the last decades of his life following his tradition in his ranch called Taimarita in Nayarit, together with his wife Xitaima Lucía Lemus de la Cruz and his extended family. Yauxali passed away from complications to cancer in 2016.

Text and Photographs ©Juan Negrín 2003 - 2024. All rights reserved digital and print.