Languages Also Die: The Case of the Wixárika

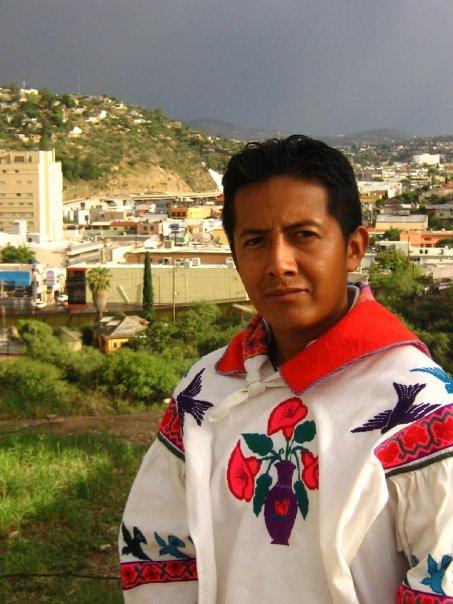

By Oscar Ukeme Bautista Muñoz

February 25th, 2008

The following exhibit can be applied not only to Wixárika (Huichol) but to any indigenous language, and is particularly dedicated to those indigenous languages in danger of becoming extinct. Only due to contextual and regional reasons have we decided to describe it and compare it in this manner. Furthermore, we are not trying to say that the Wixárika language is inferior to Spanish, to the contrary, we intend to make a fitting reflection regarding the preservation of indigenous languages. Let us thus begin.

Every February 21 we commemorate the International Mother Language Day, proclaimed in November 1999 at UNESCO’s General Conference. Languages are the principle instrument through which we can preserve and develop our tangible and intangible cultural patrimony, as they impart a basic function in the construction of our societies.

In our indigenous culture the mother tongue is the language of the gods, through it we can communicate with our deities, strengthen our customs and traditions. With it we can laugh, name things, identify spaces and places, as well as use it to sing, tell stories, and practice our quotidian dialogues.

But before continuing with our exhibit, I want to underline the following, the mother tongues of our First Nations are not dialects, they are languages with dialectic variants, which is different. Currently the General Law of Linguistic Rights of our country considers them National Languages. A dialect is a geographic variant of a language, (for example the Spanish spoken in the Dominican Republic and the Spanish spoken in Spain). The language utilized by our indigenous cultures is much more than that, it is an intellectual capacity or faculty developed as human beings that allows us to abstract, conceptualize and communicate ideas. Indigenous languages are born in a particular place and are expressed because they originate from these ancestral lands.

But let us go to what preoccupies us: languages also die. Yes, because when a language ceases from being used for a determined activity or is mixed, the language stops evolving as a means of communication within the given sphere as there are no longer new words. For example, indigenous languages rarely create new names for things that arrive in our communities such as telephones, computers, or radios. As such the language loses its influence over naming these new machines, things or items. Consequently, a “loss of dominion” is produced, first of all because these are items that are not produced by the indigenous population, and secondly because of the lack of a linguistic vision through which to identify them.

Furthermore, if we cease from using Wixárika in our daily conversations or in the workplace, little by little it becomes more difficult to speak or write in our mother tongue about recent discoveries or new knowledge, including in those situations where for different reasons it would be convenient to use Wixárika. What is happening is a deterioration of the Wixárika language as one that sustains a society, especially as we now mix it with other languages like Spanish and English. Generally speaking, there no longer are pure native languages. If when we mention words like Chat, Word, Excel, Power Point, Flash, bye, okey, Spanish has lost its dominion to English, where we have in our country more than 100 million speakers of the language, then what happens with those indigenous languages that have a much smaller quantity of speakers throughout the country where we have at least 62 native languages without counting dialectical variants, and 23 languages that are in danger of becoming extinct (cakchiquel, chichimeca, jonaz, chocho, cluj, cochimí, cucapá, guarijío, ixcateco, ixil, jacalteco, kekchí, kicapú, kiliwa, lacandón, matlatzinca, mocho, paipai, pápago, pima, quiché, seri y tlahuica)?

We have taken a few steps forward in some respects, as in the case of the System of Cultural Indigenista Radio Stations of the government’s Commission for the Development of Indigenous Peoples (CDI for its Spanish acronym) that transmit programming in mother tongues, the creation of the General Law of Linguistic Rights, indigenous books, the recording of indigenous music, and above all, the instruction of mother tongues in indigenous education, as well as the effort to standardize indigenous alphabets.

We still have much to do, and the obstacles and commitments continue to be the same ones: to strengthen and foment our mother tongues in our own homes, from parents to children, brothers and relatives, but also that of giving us the opportunity to use our languages in order to develop ourselves; otherwise we will continue to fall behind, but of course, we must place our mother tongue in the forefront.

It is possible that we wind up in a situation where Spanish or another language becomes the public language (at home, in customs, in reunions, at work, etc) while Wixárika solely remains for domestic use, for informal exchange or for occasional use. Our mother tongue can thus become an obstacle because Wixárika will cease to function as a common and rich language, and we do not want this to occur.

It is today that we must elect a language or at least recognize in which situations to use it in order to strengthen it, as tomorrow is too late. We must be informed about what is occurring and be responsible of our destiny.

Pamparios ne iwama, yu nait+ xemuye hane wixáritari aix+a xeteneu erieka.

©Oscar Ukeme Bautista Muñoz 2008

Oscar Ukeme Bautista Muñoz is a Wixárika graduate from the Autonomous University of Nayarit. He received the National Prize for Indigenous Youth and directed the Union of Indigenous Students for Mexico.

Translation by Diana Negrín da Silva