Recent History by Juan Negrín

The government has found it very difficult to ‘civilize’ the Huichol and integrate them as a dependent productive working class in the mountains. After independence was achieved from Spain, the laws of the reform passed under Benito Juárez during the 1850’s, restrained the power of the Catholic Church, but they also stopped recognizing Indian colonial land rights. Soon the Huichol, Cora, Tepehuan and Mexicanero Indian groups of the Western Sierra Madre were further dispossessed of their territory by their mixed blood neighbors. They rebelled, eventually uniting under Manuel Lozada, who joined French invading forces until they were stopped at Guadalajara, Jalisco, in 1873. Many of their land holdings were disenfranchised thereafter.

The initial impact of the Mexican revolution (1910 and the following decade) on the Huichol was not significant until the conservative Catholic population of the state of Jalisco, among others, began a grass-roots counter revolution that escalated into ‘la guerra de la cristiada’. Most Huichol were anti-cristeros, but some were convinced to join forces with the Catholics, believing that by doing so they would regain the lands they had under the colonial regime. There were internecine battles between communities, notably San Sebastián pro-cristeros against Santa Catarina anti-cristeros. The government had halted that conflict by the mid 1930’s, when Robert Mowry Zingg arrived in the Huichol territory of Tuxpan de Bolaños. Otto Klineberg also resided on an extended ranch in the community of San Sebastián for six weeks around that same time, according to data he published in “American Anthropologist”.1

The revolution established the legal grounds for improving the lot of the Indians in general, after the government theoretically began to recognize their communal land rights under President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934 to 1940). Founded on this principle the Huichol have struggled to obtain presidential resolutions that recognize the core of their colonial titles. This area amounts to less than four thousand square kilometers, a small portion of their colonial land titles.

Government bilingual schools have been introduced since the 1960’s, along with dirt landing strips, and work was initiated to improve their health care. The dirt roads, which began penetrating the periphery of their communities after the mid 1970’s, have served to enrich the neighboring lumber companies. Much of their high plateau area was then placed under territorial dispute, while the old trees along the shoulders of the roads were plundered without any benefit to the Huichol. Cattle-grazing is also beginning to take its toll further eroding the soil, and diseases like tuberculosis are spreading.

During the recent past the Wixaritari have adapted to change by concentrating on their values and exploring the rest of the world with dignity. They have been ingenious in escaping deep acculturation and retain an alternative culture by relying on their traditional leaders, now backed by an intelligentsia of more literate members linked to the outside world. Three new leaders were elected by consensus for three year terms at each community headquarter to correspond with the National Institute of Indian affairs once it started functioning in 1951. They formed a body called the ‘presidencia de bienes comunales’ headed by the president of communal goods, who worked in agreement with the traditional authorities.

Land was rescued with the government’s backing, although the Indians were not always happy with the intermediaries the government chose. The most famous among them is Pedro de Haro, about whom Fernando Benítez writes, and who reclaimed a lot of land for the community of San Sebastián.2 He served in the unique position of president of the supreme council of the Huichol, until the government replaced him in 1976.His successor was hand picked by outsiders and served poorly for 9 years, while the forests were plundered and renting grazing lands to Mexican neighbors was encouraged. The position of supreme council was finally eliminated after a series of legal confrontations in 1985.

The traditional authorities and the council of elders have been ignored by Mexican authorities since the beginning of the 1990’s, when the government centralized the Wixaritari of Jalisco in an organization called Union of Indigenous Communities of Jalisco (U.C.I.J.), promoting a new top leader as its president each year from one of the Huichol communities in the state.

Outsiders ignore the Wixaritari today as much as ever. So-called ethnographers quote them talking about a pantheon of gods and goddesses, when these terms do not really correspond to their native language. They simplistically repeat what honest naturalists and explorers, like Lumholtz or the first ethnographers, like Diguet and Preuss, had researched between 1895 and 1907, then Zingg in 1934.

The Wixaritari are amused, when they are not irritated, by the vast array of people who only associate them with the peyote cult of their purportedly folkloristic culture. Serious researchers never gave them credit for even having a notion of how to use verbs in their language, to the extent that Diguet decided to try to teach them how to conjugate an equivalent of the verb ‘to be’, so they could better express themselves. Thanks to McInctosh and Grimes, in the late 1950’s, westerners recognized these people have a sophisticated grammar, although their labor was done for evangelistic purposes and they never pretended to study Wixárika religious terminology in depth.

As Jay Fikes points out in his book,3 other anthropologists have acquired fame without even exploring the Wixárika within their territory. Finally, new research is being carried out on their language that is likely to yield interesting fruits at the University of Guadalajara, under José Luis Iturrioz Leza. The Mexican government has made it clear to the Huichol that any outside visitor to their communities may be denied entry, particularly foreigners. Thus in some way, the government reinforced the powers of the traditional authorities to maintain a nation within a nation.

Photograph ©Juan Negrín 1986 - 2023

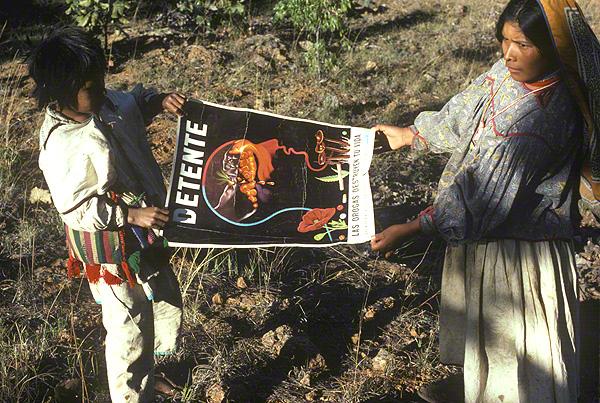

Today, powerful outside forces are surrounding them with great scourges like drug plantations of poppies and marihuana. Others are pushing pesticides and herbicides without any precautions, causing a great rise in the rate of cancer among this previously healthy population.4 The latter substances were introduced under the government’s sponsorship on a large scale, impoverishing the biosphere of complementary nutritive resources, like the spring-onions and the small tomatoes, and depleting the flora of Indian carnations.

Major plans are underway since February of 2003 to build a new maintenance road for electric posts and cables that is meant to stretch through the heart of the Wixárika territory, bulldozing and dynamiting through their deep cave centers for the first time, to connect the northwest and the southeast. In the midst of this new road are sacred spots surrounding Teakata, where the natives were purported to have united to resist the Chalchihuites Empire in the time of the Toltecs (see Early History). As you may read in the current news section, the community it affects most directly had asked the government to stop its road works in that area and to suspend the electrification program because of its proximity to sacred sites used for educational and spiritual purposes by the Wixaritari. Recent news is that the road will not be suspended because some native authorities were successfully lobbied to have its central section built without ever being informed about how they will lose all property rights along its path.

Equally distressing is the news that the World Bank has offered the current Mexican government the necessary credits to build the country’s second tallest hydroelectric dam, called El Cajón, in Santa María del Oro, an archaeological site near the mouth of the river into which the Huichol canyon flows. Its main wall is supposed to be 186 meters high, practically as tall as Aguamilpa’s, the highest dam in the world. That would represent an overwhelming ecological and cultural devastation, as we can foresee the water tables rise and plunge unexpectedly. The work has begun with local opposition from peasants, who have lost their land without redemption, and it is flaunted as the current administration’s major economic feat. The site of the El Cajón Dam is only 50 miles inland from where the gigantic dam of Aguamilpa was finished in 1995 and taps into the same water resources.

1 Dr. Phil Weigand, Personal communication.

3 Academic opportunism and the psychedelic sixties

4 Plaguicidas, tabaco y salud, Patricia Díaz Romo y Samuel Salinas Álvarez[1] Academic opportunism and the psychedelic sixties

Photographs and Text ©Juan Negrín 2003 - 2023, All rights digital and print reserved.

Bibliography:

Fernando Benítez, Los Indios de México, Volume II, Ediciones ERA, S.A., Mexico, 1971

Patricia Díaz Romo y Samuel Salinas Álvarez: “Plaguicidas, tabaco y salud: el caso de los jornaleros huicholes, jornaleros mestizos y ejidatarios en Nayarit, México, 2002. Proyecto Huicholes y Plaguicidas

Léon Diguet : « Idiome Huitchol-Contribution à l’étude des langues mexicaines » Extrait du Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris. Nouvelle série, tome VIII, 1911.

Jay C. Fikes, Carlos Castaneda, Academic Opportunism and the Psychedelic Sixties, Millenia Press 1993

Carl Lumholtz, M.A., Unknown Mexico, Volume II. London-Macmillan and Co., Limited. 1903.

Carl Lumholtz, M.A.: “Symbolism of the Huichol Indians”, Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, Volume III, Anthropology II, May 1900

Konrad Theodor Preuss: “Fiesta, literatura y magia en el Nayarit. Ensayos sobre coras, huicholes y mexicaneros de Konrad Theodor Preuss” Jesús Jáuregui y Johannes Neurath. Compiladores. Instituto Nacional Indigenista. Centro Francés de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos. 1998

Beatriz Rojas: “Los Huicholes en la Historia” Centro de Estudios Mexicanos y Centroamericanos/El Colegio de Michoacán/Instituto Nacional Indigenista, 1993