Psychedelics, the War on Drugs, and Violence in Latin America

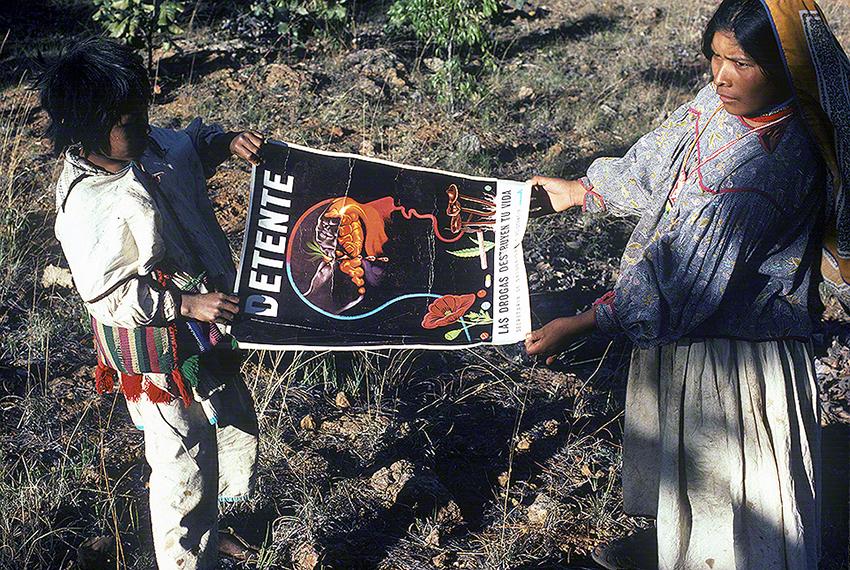

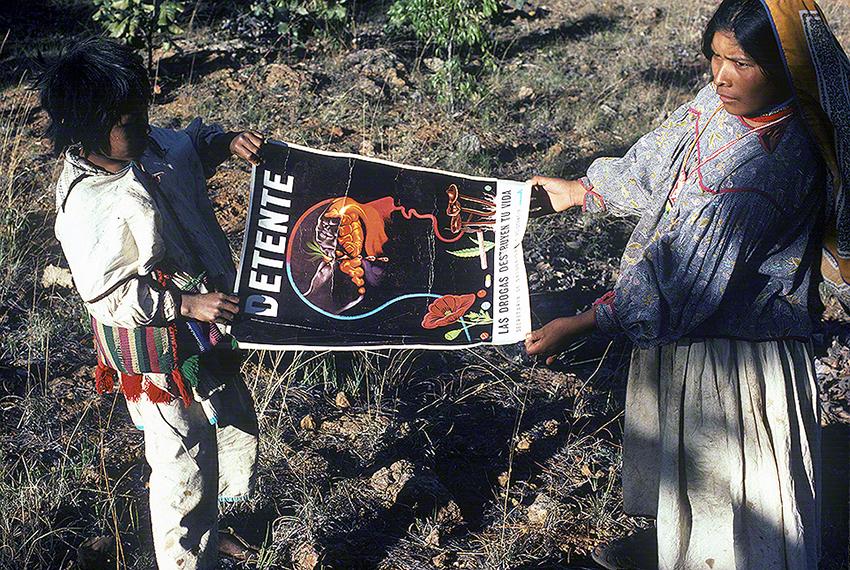

On September 22, 2021, six young Wixarika men between the ages of 16 and 32 were “disappeared” from a road that runs along the sinuous border between the western Mexican states of Jalisco and Zacatecas. Relatives and friends confirm that the young men had gone to carry out a traditional deer hunt. Within days, four of the six bodies were found bearing the marks of torture that are all too common in a country that acts as a hub for organized crime serving its northern neighbor’s notorious appetite for drugs. The threat of violence caused by the taking of land for cultivation, the use of roads to move product, and the capture of labor by these agents has created an intolerable environment for the Wixarika people.

Since September, many more Wixarika men and teenagers have disappeared and been murdered; most recently, Rosendo González Torres, a mara’akame (chanter and healer) and his 17-year-old grandson. The incident barely made a note in the press or on social media, despite González having traveled to provide his cultural services abroad. This is the reality for the Wixarika and their other Indigenous neighbors, the Naayeri (Cora) and Odam (Tepehuan) whose Western Sierra Madre homelands have often been affected by illicit drug trafficking. This is also the reality for countless other Indigenous and small farmer communities across Mexico and the Americas.

For several years, I have grown concerned over the parallels that the present commercialization of psychedelics and sacred plants might have with the decades of violence that stem from the commercialization of other substances. It is rare to see the global public take note of the overwhelming violence that Indigenous peoples continue to face as their territories are targeted for the extraction of oil and metals, or their land is reconfigured at the service of the palm oil industry or the opiates market. Many of the communities who have ancestrally lived on these territories are sought after by a variety of actors interested in their ceremonial and therapeutic uses of plants with hallucinogenic properties. And yet, psychedelics enthusiasts appear to bypass, if not fully neglect, how the mainstreaming of these plants and animals is reshaping local economies, disrupting social relations, and impacting ecologies. This occurs in the context of the larger narcotics market that remains the greatest success story of psychotropic pharmacopoeia.

Miguel Evanjoy of the Union of Indigenous Yagé Doctors of the Colombian Amazon is one of the people who has most eloquently exposed this contrast by locating the current boom in the “medicalization” of yagé within a longer history of deeply extractive practices. The Putumayo region has survived one extractive industry after another and hundreds of years of associated violence catalyzed by the invasions of the rubber and cocaine economies—to name only two. Initially a medicinal plant of varied use, coca (like tobacco) became disassociated from its traditional and culturally mediated uses and harvests. The colonial mines pushed its use to sustain brutal hours of extraction and, by the late twentieth century, its processed variants became global commodities that provided exponential and legendary profits to a few. It is a great tragedy of our modern history that we have transformed something healing into a poison.

One of the take-away points made by Richard Evan Schultes and Albert Hoffman in their celebrated book, Plants of the Gods (1979), is that plants contain numerous toxins and, therefore, their human ingestion has historically been mediated by the often-cited terms of “dose,” “set” and “setting.” In his 1987 San Francisco State University lectures, published in The Nature of Drugs (2020), Alexander Shulgin approaches the world of drugs as an opportunity to reflect upon and better educate ourselves about our relationship with the substances we ingest—even everyday substances we take for granted and do not typically identify as “drugs.” Shulgin notes that our bodies are complex and our relationships with different substances can have different purposes and effects, be they healing or harmful. Beyond these basic points noted by these prominent authors, it is fundamental to pause and reflect on the domino effect caused by the consumption of psychedelics and the cartographies that are shaped by the movement of a substance, be it a plant or a chemical.

I currently live in the San Francisco Bay; undeniably, one of the most emblematic places in the history of psychedelics. The late 1960s cemented San Francisco as the birthplace of free love, psychedelic light shows, and a euphoria surrounding collective tripping. LSD was the main protagonist, and many recount that it did not take long for the public to turn to other substances, some of them deeply destructive. Here, the 1970s are spoken of as the beginning of the end of the psychedelic peace and love movement and the degradation of many other social movements. It is a period marked by the beginning of Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs” as a powerful state policy that incentivized the rise of the prison industrial complex and the flow of weapons and transnational mafias. By the 1970s and 1980s, the slow deaths caused by drug addiction penetrated the streetscapes that had previously held political rallies and spontaneous concerts.

It is said that the pandemic has sharpened our thirst for pills, liquor, marijuana, and even ayahuasca ceremonies. San Francisco is now the public face of the drug crisis—its downtown streets and the encampments that hug its freeway system are an inescapable reality in one of the most expensive regions in the world. Reports abound that indicate how, even during the height of COVID-19 infections in 2021, there remained more cases of deaths by overdose than by the virus. The most recent numbers tell of a 30% increase in overdose deaths: 93,000 in 2020 in the United States from opioids alone! We struggle with the reality that many young people we know are dying from overdoses from these powerful pills.

The other side of this story is experienced daily in the towns of Mexico, from the presence of crystal meth that has already penetrated several communities, to the disappearance of young people forced to work in drug fields. I want to emphasize that the current generation of young people—particularly youth of Indigenous and African descent—is experiencing a landscape invaded by the heavy hand of the illicit industry that moves things, people, money, lives, and deaths.

One such example can be found in the Yaqui communities of Sonora, where the struggle for the right to territory and water has been a constant factor since the era of European colonization, and where drug addiction and the prevailing shadow of various cartels have been the most recent invasions. One does not know if men are being disappeared and murdered because of their affiliation with the defense of their territory or as a result of the reign that organized crime has along the peripheries of these ancestral communities. Dispossession has taken many forms and has happened at the hands of various agents and institutions, and yet we hardly face the “unseen” effects of our consumptions. What will happen when we want access to larger quantities of ayahuasca, peyote, kambô, or ibogaine? What will be the chain of production or the political, economic, and social domino effect that we unleash through our consumptive practices?

Cartographies of Desire and Dispossession

We shouldn’t be surprised by the success of artists like Natanael Cano, who created the trap- and corrido-inspired genre of the “corrido tumbado” in California that is now heard in the neighborhoods of Sacramento and Zacatecas. Drugs—those we often call our medicines—and our affection for them is a popular topic, like the red plastic cups in music videos. In recent conversations with writer Roberto Lovato regarding the “gentrification of consciousness,” I shared my fear of an even more dystopian world, one in which some sacred plants will see a future where they are valued just like coffee, soybeans, marijuana, and other great monocultures produced from dispossessed lands and bodies in Abya Yala. They produce the same historical paths where the South feeds the North at quite high costs. Mazatec anthropologist, Osiris García, makes this point with respect to the shared routes of coffee and psylocibin mushrooms, once we analyze the system of power that is divvied up between caciques (local bosses) and landowners, regional politicians, and business agents at various scales.

Some certainly welcome the economic derivatives that have come with the proliferated use of ayahuasca, psylocibin mushrooms, and the Bufo Alvarius toad. This economy includes fees for shamans, materials for ceremonies, luxury retreats and rustic gatherings, travel costs, fees for musicians and massage therapists, the sale of crafts, and new wellness brands and products. We live in a moment in which we are at the dawn of what seems to be a revolution in the world of the normative consumption of hallucinogenic plants and analogous chemical substances. The new Dr. Bronner’s soap labels attest to the promise, as do Michael Pollan’s two most recent books, the numerous university sponsored research initiatives, and accompanying legislative reforms seeking to decriminalize psychedelics.

It is therefore urgent to be attentive to the current landscape of actors and activities associated with psychedelic research, funding, production, and legislation, for it can tell us a lot about the reproduction of power and interests involved in what is an otherwise vanguard movement. This is why it is imperative to ask ourselves how the worlds of consumption of plants sacred to Indigenous peoples coexist or are affected by these trends in their endemic places, in their places of commercial cultivation, and in the geographies where chemical analogs are produced. As the Tukana artist and activist, Daiara Tukano, affirms in an interview with Chacruna, the native communities of the Amazon and their ancient traditions with psychotropic plants are not going to cure the problems of the people of the North, and they are not going to alleviate the glaring mental health crisis elsewhere. With this in mind, I close this reflection calling for more intentional dialogue within the psychedelic community about the realities caused by the history of trafficking of other substances in order to better understand the centrality of the struggles for territory, for water, for forests and the right of autonomy for Indigenous peoples. This dialogue is imperative; otherwise, I am afraid that the celebrated psychedelic renaissance will bear responsibility for contributing to new chapters of human, cultural, and environmental dispossession.

References

Schultes, R. E., & Hoffman, A. (1970). Plants of the gods. McGraw Hill.

—

Note: This article was originally published in Chacruna Latinoamérica.